Narita Boy Review (PS4) – //: Beyond The Source Code

Four years after its Kickstarter, 2D adventure Narita Boy is finally here. The world of the Digital Kingdom is certainly striking, but does it live up to its promise? The Finger Guns Review.

For many of us, games are escapism, pure and simple. You press that power button, hear the startup chime on your flashy console, and you know you’re about to get whisked away from your everyday life. It’s time to be a warrior, a tomb raider, a superhero, a Narita Boy, anything but yourself. And that world is being created inside that console, somewhere beyond the screen. It’s a technological Narnia where from the moment you boot up a game, or slot in a quarter, you’re somewhere else.

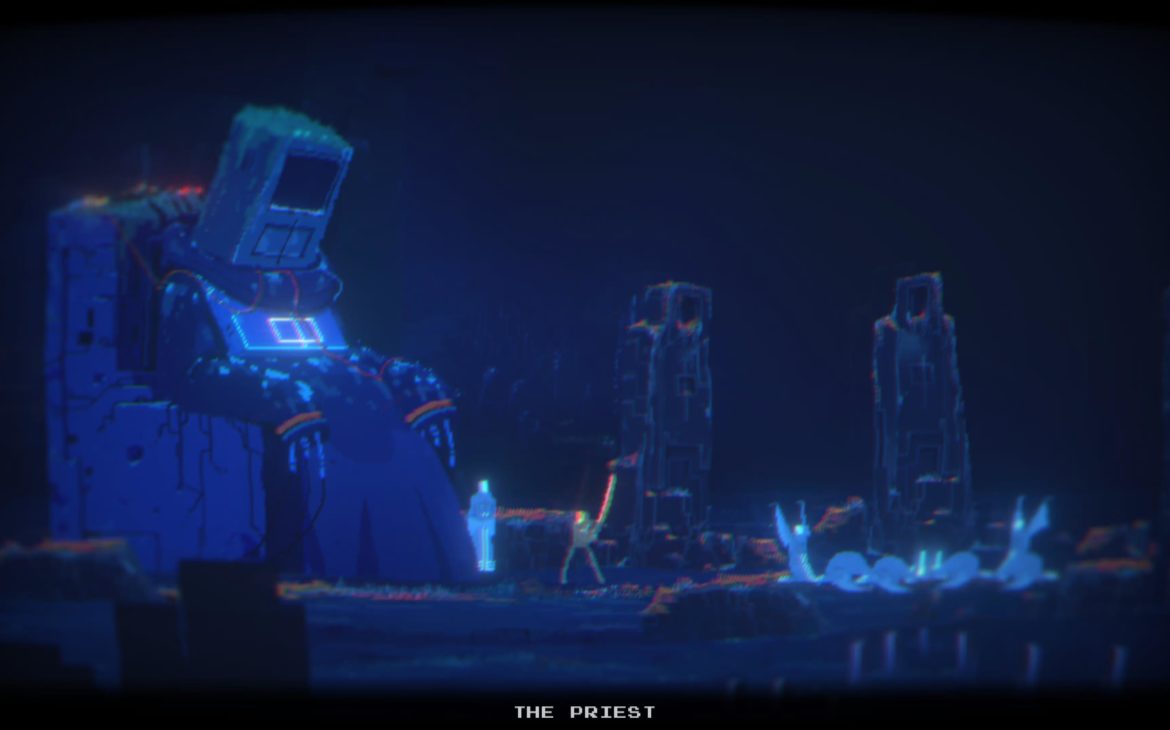

Narita Boy aims to do something special. It takes the escapism, that world beyond the screen and it mythologises it. It’s a distillation of Tron and The Dark Crystal, combining high fantasy with retro sci-fi in a way that’s somehow modern and ancient at the same time. Myth rather than simple narrative. Essential and primitive. It’s like the world inside Daft Punk’s helmets. It’s the Never-Ending Story crossed with the Matrix. Heroes from outside the world coming in to save it.

Part Metroidvania, part 2D adventure platformer, Narita Boy lures you in with its striking pixelart visuals, and distinct synth soundtrack. Does it live up to the four year wait if you were part of the kickstarter, or is it a disappointment?

The narrative of Narita Boy is probably its strongest element, so let’s start there. Back in the 1980s (because everything recently is set then) a genius developer referred to simply as the Creator, invented the Narita One console and a game called Narita Boy. It was a hit, propelling him to geek stardom, but his life wasn’t as rosy as the media made it seem. Meanwhile the Digital Kingdom, the world of the Narita Boy game, had transcended its binary code and become a real place, existing within the digital realm, so strong was the creator’s vision we assume.

When one of the program supervisors, HIM, of the Trichroma, the three-coloured force at the centre of the Digital Kingdom, decides he can rule over all, he reaches across the realms, through the 4th wall and injures the mind of the Creator, shattering his memories and spelling doom for the Digital Kingdom. Only a backup code, created to summon a hero from the real world, can hope to save it.

You play as Narita Boy, the fabled hero from beyond the source code. While innocently playing video games, you’ve been whisked into the Digital Kingdom to live out the ultimate escapist fantasy. He is like Bastion become Atreyu in the Neverending Story, or Neo come to free the Matrix, a mythical messiah character. 20 pixels of condensed power, he is the only one who can wield the Techno Sword and stop HIM from destroying everything. So yeah, only the very existence of the Digital Kingdom is at stake.

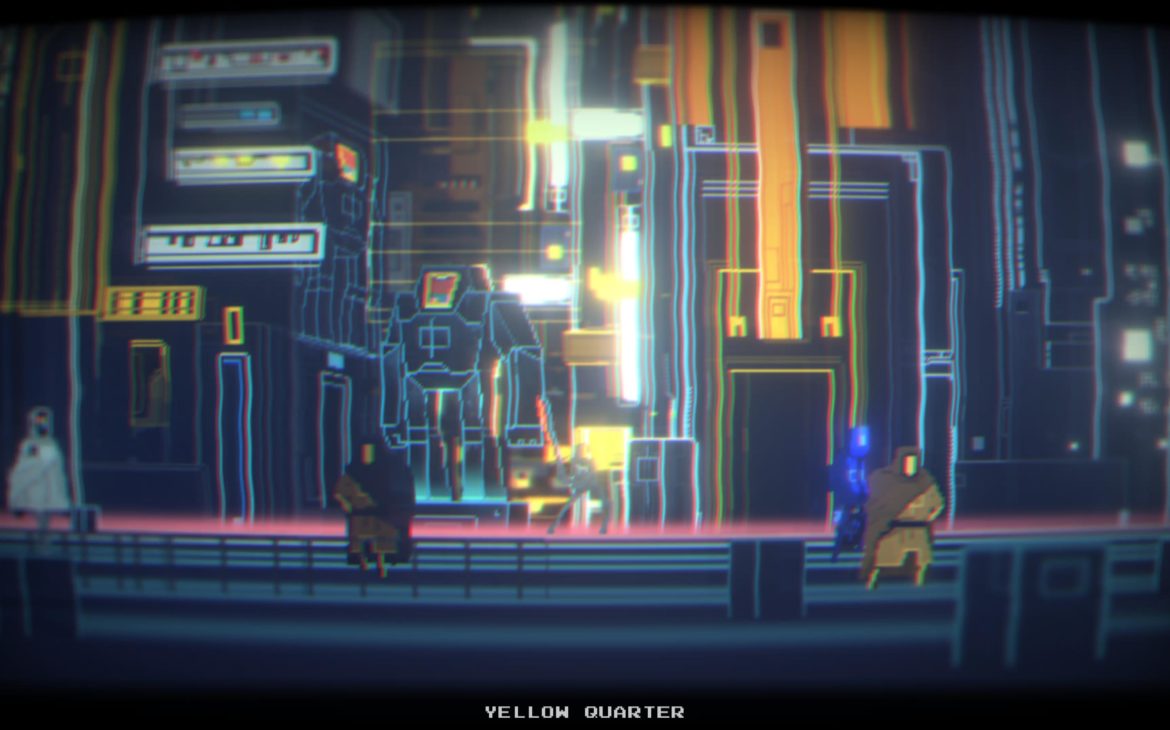

It’s ambitious and heady stuff, setting you on a journey across five different realms including the yellow, red and blue beams of the Trichroma, whose energy powers everything. There’s lore everywhere, so much so that my short explanation here barely scratches the surface of the deep mythical feel of the narrative in this game. Narita Boy employs that Matrix/Tron idea that all characters and NPCs are code, programs written with specific purposes. But here it’s elevated, given ancient substance, through a high fantasy lens. It’s a stellar piece of world-building that just effortlessly draws you in, even if for some, the masses of expository dialogue from NPCs, priests, and strange programs will be a turn-off.

Narita Boy’s job is to find the shattered memories of the Creator and piece them back together, restoring his mind and saving the world. At the same time the Red Stallions, the army of HIM, stand in your way. It’s set up like a metroidvania, but a metroidvania in five stages. As you traverse the world, you will meet NPCs, one strange digital being after another, collecting technokeys (floppy disks) to unlock your way to the next. You will backtrack quite often to use these technokeys to progress. However, at the end of each realm, you will move on, never to return in that playthrough. This is why I say a metroidvania in stages, rather than a true one.

At times it can feel fairly linear because of this, but on the other hand this does a lot to streamline the experience. There will only be rare stages when you don’t know where to go. Keep track of the pedestals for installing floppy disks and doors you haven’t opened yet, and each part of the journey just flows to the next, to the next.

The memories you find also form a coherent, interesting, and often poignant backstory of the creator’s life, his programming of a hit videogame, and how the red beam code ruined his life. It’s told through stunning pixelart dioramas that you walk through reading narration from the creator with a wonderful synth lullaby scoring the story.

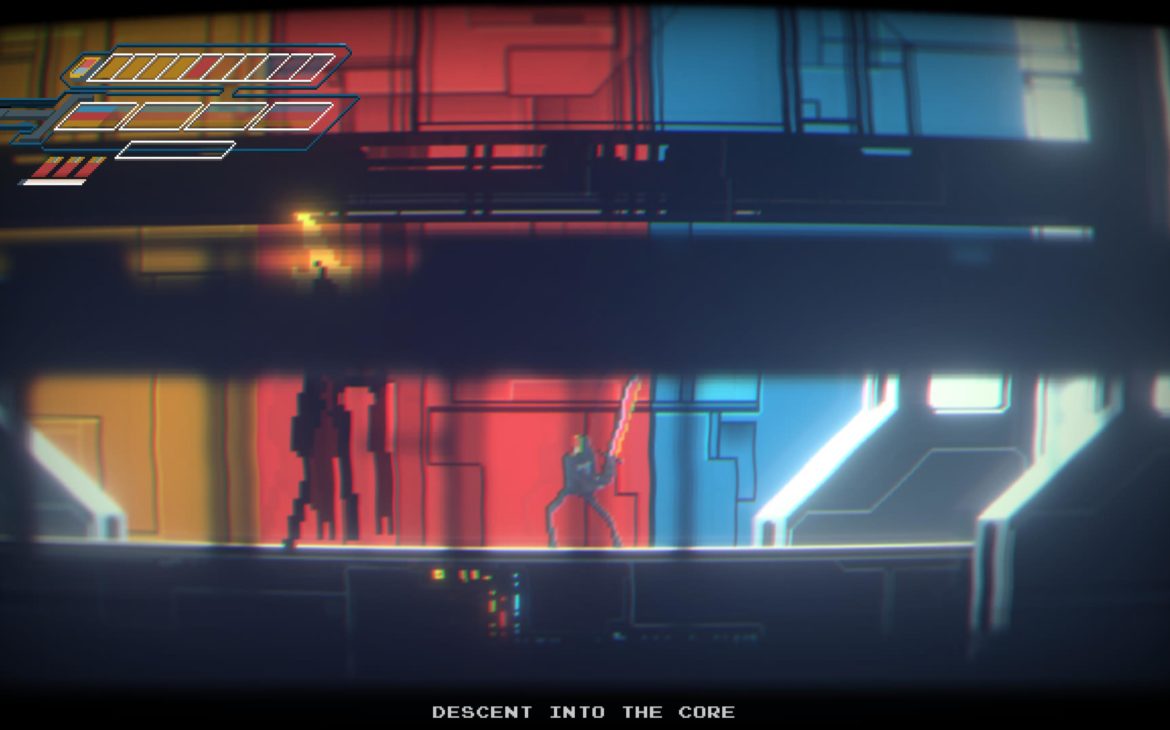

As you progress, you will discover floppy disks for powerups and combat moves. Starting with the Techno Sword, forged from the three beams of the Trichroma, through dodges, shoulder-bashes and smash-stabs, you’ll finish the game a powerhouse of moves able to employ them all to your advantage. The pace is really good, meting out new stuff every half an hour or less.

Using those moves, Narita Boy has some really satisfying 2D combat that never gets too complex. There’s no RPG mechanics or levelling, you just get better with practice. The enemy Stallions are also well designed so that almost every type has a different optimum kill method; whether that means constant dodging and weaving round the hammer wielders, or stab-smashing the armour off the Iron Jelly men, they are constantly inventive and wildly fun to fight. Strangely you don’t gain anything from combat, no souls, no levels, nothing. You can build up a meter that allows you to heal a little, or summon a bit of help from three Trichroma dudes you’ll meet on your journey, but that’s all. Because of this, most combat is framed on particular screens as challenges and you are not able to skip it at all.

There are also a lot of bosses, probably three or four per realm, and plenty of other enemy groups to chip your teeth on. This stage-like structure extends to many of the stranger powerups – the ones that often don’t affect combat. Each realm seems to build towards a particular device or technokey that is used to traverse an inhospitable area, and reach the next. For example in the yellow realm you eventually unlock the use of the servohorse (a horse with an apple computer for a face) to ride, or in the blue realm a very cool floppy disk hoverboard. Each of these lead to a 2D challenge gauntlet using your new powerup. The only real shame here is that each one is barely touched again after that section is complete.

On your journey you will encounter a series of colourful teleport stations that you can use to reach new areas, and each one is worked using a symbol code. These puzzles involve you keeping your eyes peeled throughout the realm that you are exploring for the the right symbols in the right colours to unlock the teleporters. I found this mechanic fun in a very interactive retro way, having to actually keep a post-it note of esoteric notations of symbols so that I could keep track of them. They aren’t complex, but there’s lots of them, and you’ll struggle to remember them all. This really gave it a retro feel – I haven’t had to mark up a notepad while playing anything for years.

All these systems function well and despite small gripes are largely great to play. Where Narita Boy falters a little is in its simplistic platforming. You will jump and uppercut slash your way across some platforming sections, or employ a climbing mechanic to reach some high areas. While none are complex enough to prove a challenge, therein also lies the problem. The platforming is just far too simplistic, barely involving much in the way of skill to complete. Its very forgiving, often allowing jumps to start after you’ve long since left a ledge, and you’ll rarely have to redo more than one screen area if you do die. It just seems a shame that a game so innovative and unique in other places fails to implement anything but the most basic 2D platforming. I could also easily accept an argument that the game is much more focussed on story, combat and exploration, and that platforming came a poor fourth in development.

Narita Boy is not just conceptually stunning, it’s also visually stunning. Just look at some of these screenshots. The Digital Kingdom is a world full of incredible art direction, vibrant use of colour, unique creature design, and beautiful polished pixelart animation. There are simply dozens of areas, rooms and screens that will look incredible to pixelart lovers. Many would be the best screen in an entire lesser game, but here they come and go, and then its on to the next. There are so many of them, there’s no time for anything to stick around. It’s just a constant flood of beautiful images to your visual cortex.

The creatures, enemies and NPCs are truly jaw-dropping, evoking a truly separate ecosystem, where the digital and the fantasy collide. Animals with old apple computer screens for faces, a frog whose throat is a bulging Tron grid, the pulsing CRT screen effects, forests where digital water flows and flashes. There’s a little of the Sword and Sworcery Superbrothers feel to some of the designs, especially Narita Boy himself, and this is only a compliment.

It’s a beautifully realised creation, a feat of world-building imagination and artistic skill, that will wow you all the way through. It’s holistic in that every visual ties together with the lore of the world, the story of Narita Boy, and the mythology, only here you can see it instead of read about it.

Narita Boy also has some stunning sound direction. Salvinsky is the brother of the guy who dreamt up most of the Trichroma and Narita Boy’s world, and he scored the whole thing. It’s an incredible soundtrack, full of some of the most evocative and complex synthwave I’ve heard since DisasterPeace did Fez and Hyper Light Drifter, or Lena Raine on Celeste. There are plenty of really clever and quite abrupt synth noises in there that I’ve just never heard before. Each realm has a theme that ties in perfectly with making you feel a certain way while there; spooky refrains in the early Creator’s Tears areas, synth lullabies in the forest and the Creator’s memories, harder synth battle themes for the game’s intense bosses. It’s a gorgeous soundtrack that is sure to have a life of its own outside the game. I know it’ll go straight into my rotation on Spotify the moment it releases.

Salvinsky himself even has a small cameo in the game, appearing as the Synth-Sensei (see above) just ahead of the gates to the three Trichroma realms, composing the score to the journey of Narita Boy even is it unfolds.

The sound design is also noteworthy. The sounds for monks and priests chanting all sound like they come from another world, modulated and digital. The glitches and powerup sounds are all unique and original. The whole thing is holistic again in the same way as the visuals and concept, all tying together into unified sound and vision.

Somehow more than its source code, Narita Boy is a game that manages to be more than the sum of its parts. It’s unified vision for the world of the Digital Kingdom is up there with some of the best art direction, sound design and conceptual world-building I’ve ever seen. The world and lore manages to transcend into the realms of mythology, something I’m not sure I’ve felt before in any game. It’s somehow ancient and primal, the digital combined with high fantasy to incredible effect.

Beyond its concept, it manages to be a tightly designed eight hours of exploration and discovery, that its fantastically paced and rewards you constantly. It never outstays its welcome, and moves on to the next of its wonders with precision and skill. Combat is fluid and fun, responsive and complex and full of all the things we’ve come to expect from modern combat design.

No game is perfect and Narita Boy could have done with a little more freedom in its quest design, and more interesting platforming, but I don’t think on their own those things are actually detrimental to the overall experience. As I said, it’s more than the sum of its parts, which means even weaker sections can be elevated when part of the whole experience.

Narita Boy is a feat of imagination, one of the most conceptually interesting games I’ve ever played. The retro world of the Digital Kingdom – its pixelart, design and art direction – are some of the most eye-catchingly beautiful ever committed to code. Its soundtrack is mesmerising, truly special synthwave. Narita Boy ends up more than the sum of its parts, going beyond the source code to deliver a game that should take its place alongside the greatest indies.

Narita Boy launches March 30th 2021 on PS4, PS5 (review platform), Xbox One (also with GamePass), Xbox Series S/X, PC via Steam and Nintendo Switch.

Developer: Studio Koba

Publisher: Team 17

Disclaimer: In order to complete this review, we were provided with a promotional copy of the game. For our full review policy, please go here.

If you enjoyed this article or any more of our content, please consider our Patreon.

Make sure to follow Finger Guns on our social channels –Twitter, Facebook, Twitch, Spotify or Apple Podcasts – to keep up to date on our news, reviews and features.